A few months ago, as I was walking down the aisles of a professional fair for public sector decision makers, I noticed two main themes on display:

- Cybersecurity, from secure citizen identity verification to the resilience of systems and data to threats.

- Efficiency of public services, with an emphasis on the need to better leverage and share data.

As a public decision maker, I would be lost, if not paralysed by, the contradiction of being asked to modernise my systems and organisation through better use of data and data sharing, while being constantly reminded that cyberthreats (and cyber attacks) are everywhere.

The first months of 2023 have been characterised by two sub-topics that illustrate this bipolarity: digital sovereignty (a country’s capacity for self-determination and in some cases data protection and isolation) and generative AI (a platform’s capacity to have access to all the data you might collect and extract, and lever this information to turn it into intelligible insights).

To bring these together, we felt something was needed and that some well-implemented borders and security measures are needed to be reconsidered.

An Inflection Point in the Importance of Data

Governments have long classified data primarily on its sensitivity. The UK government’s security classification, for example, defines “the sensitivity of information (in terms of the likely impact resulting from compromise, loss or misuse) and the need to defend against a broad profile of applicable threats.” Based on that definition of sensitivity, UK government policy applies three levels of classification for government data: top secret, secret and official. The majority of EU governments have also classified the data they manage based on sensitivity.

This classification showed its limits in February 2022 when Ukraine rushed to identify and migrate strategic data assets critical for the government to enable operational continuity and bolster resilience. Previously, Ukrainian law required some government data to be stored in local servers in Ukraine, but this was changed a week before the invasion. Essential data has already been migrated from over 27 Ukrainian ministries.

IDC analysis shows the public sector is at an inflection point when it comes to the importance of data, and that it’s not only a matter of protecting sensitive data but also of anticipation. This is done by recognising data as a critical and strategic asset for governments to function more efficiently, effectively and resiliently to deliver the outcomes and security solutions that citizens expect, in times of crisis and on a daily basis.

A Framework to Facilitate Readiness

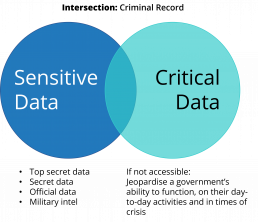

This has led us to create a framework that builds a new layer in data classification. In our Learning from Ukraine: Building a Framework to Safeguard Governments’ Critical Data, we recommend that governments not only classify and manage sensitive data but also critical and value-added data.

Critical data can be defined as data that if not accessible or not reliable can jeopardise a government’s ability to function in its daily activities and in times of crisis. It’s important to highlight this difference between classifying data based on the level of sensitivity and the level of criticality because some data sets have both characteristics.

For example, a criminal record is both sensitive (because it contains personal information) and critical for the criminal justice system to function. However, land registry data does not contain the most sensitive information but is critically important to determine jurisdictional boundaries, settle property disputes and assess the value of taxable assets.

Bringing Everyone on Board

Data sharing and interoperability and the building of European data spaces are vital here; sovereignty (the capacity to self-determine your action) should serve this cause and not get in the way, as it is often confused with security.

Sovereignty is a current concern as many government entities are seeking to update their cloud policies, such as the “Cloud au Centre” in France and “cloud first” in the UK. Some initiatives also promote interoperability, with Portugal’s eSPap government authority developing a platform for public entities.

These initiatives aim to bring more coherence to IT systems and enable new services in healthcare and security, for example.

Local governments are still trailing European or central governments when it comes to transformation, partly due to trust issues. We believe that enabling this new layer of criticality, and adapting our framework for every local public entity CIO, will be key to creating a common secure language.

To learn more about government’s role in safeguarding critical data, see our new study Learning from Ukraine: Building a Framework to Safeguard Governments’ Critical Data and join us at the IDC Government Xchange.