Data is NOT the new oil, but it has VALUE. But what can European policymakers do to realise that value? Policymakers across the globe have been grappling with the complex question of the data economy for a few years. Simplistic, hype-creating statements like “data is the new oil” or “data is the lifeblood of economic development” can be misleading.

Policymakers need clarity when making critical decisions. Here, we propose a framework that European policymakers can use to make decisions to realise the value of the data economy for all and put the rights of the individual at the centre.

How Countries Are Approaching Data Policy

Countries like the United States have taken a liberal approach to the data economy. Companies have a free hand to collect and use data.

But policymakers are starting to grapple with ethical implications. Other countries, like China, have taken an autocratic approach — the government exerts central control.

The European Union wants to boost the data economy while putting the fundamental rights of the individual at the centre. In fact, the European Commission’s European Strategy for Data aims to give businesses in the EU the possibility to build on the scale of the single market.

The EU’s stated aim is that “Common European rules and efficient enforcement mechanisms should ensure that:

– data can flow within the EU and across sectors;

– European rules and values, in particular personal data protection, consumer protection legislation and competition law, are fully respected.

– the rules for access to and use of data are fair, practical and clear. Also, that there are clear and trustworthy data governance mechanisms in place (there is an open, but assertive approach to international data flows, based on European values).”

What is the Value of Data — Clearing the Hype Around “Data is the New Oil”

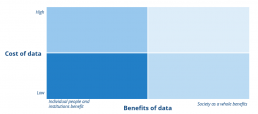

To clear the hype around the data economy, we need to go back to the fundamental question of VALUE. If we agree that data is a strategic asset that requires a dedicated EU policy, it is because it has value. Value needs to be considered from two different perspectives:

The Effort/Cost Perspective

Governments, industry, and academia invest money, time, and knowledge in collecting, aggregating, archiving, sharing, analysing, and securing data.

Costs are both tangible in terms of investing in people, processes, and technology and intangible. For instance, the fact that people are concerned about privacy makes compromise politically costly.

Institutions that make these investments deserve fair compensation for their efforts. Overall, the marginal cost of technology involved in collecting, aggregating, analysing, and securing data is falling, but there are important differences.

For instance, the effort to analyse climate patterns, or genomics, or to design the next spacecraft is higher than the effort that a bank makes to calculate an investment fund portfolio performance. For use cases where the effort is higher, only a few companies or institutions have the resources to build a viable market offerings.

And this limits competition. For use cases where the effort is lower, the barriers to entry in the market are lower, thus more competitive offerings are available.

The Benefit Perspective

The intelligent use of data can make a big difference in terms of quality of outcome or efficiency of processes. Users could also assign higher value to data if it were scarce.

However, data scarcity is NOT a problem, quite the opposite, which rules out the simplistic view that “data is the new oil”. Quality and efficiency benefits can be differentiated based on whether they impact individual people and institutions or society as a whole, such as sharing data among hospital labs across Europe (and the globe) to speed up the discovery of a vaccine for COVID-19. This has bigger value for society than, let’s say, monitoring the number of defective products coming out of a manufacturing line that builds chairs.

Of course, knowing if there’s a broken chair is valuable for society. It makes a company more efficient, therefore increasing economic wellbeing. And fewer broken chairs mean less need of medical assistance. But it is a long-winded, indirect societal impact.

For use cases where data generates public good, convenient, trusted, transparent and affordable access to it should prevail. For use cases where the benefit is only for an individual person or institution, the right to protect the individual or the company’s rights should prevail.

A Value-Based Framework for Data Economy Policy Making

The combination of the effort and the benefit perspectives provides a useful framework to guide policy decisions.

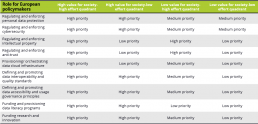

- For use cases that require greater effort and deliver societal benefits: European policymakers should establish the technical/semantic/organisational interoperability standards. They should set data protection and cybersecurity rules. They should build or orchestrate data management and usage capabilities, by investing in federated data cloud infrastructures, because there is a higher risk that society will become dependent on a few oligopolists. Otherwise efficient, data-driven innovation will slow down.

- For use cases that require greater effort but deliver value to individuals or small groups: European policymakers should define and enforce clear antitrust rules to ensure that oligopolists do not end up stopping innovation. They should set data protection rules to avoid the infringement of fundamental rights of the individuals. They must promote higher data literacy. But they would not need to intervene to deliver data collection, exchange, and usage capabilities.

- For use cases that require lower effort but deliver societal benefit: European policymakers should establish the technical/semantic/organisational interoperability standards, and data protection and cybersecurity rules. But they shouldn’t worry about controlling market competitiveness or delivering capabilities.

- For use cases that require lower effort and deliver value to individuals or small groups: European policymakers should establish some basic data protection and intellectual property and cybersecurity rules.

European policymakers can start to apply the framework to the nine data spaces in which the European data strategy aims to invest — industrial/manufacturing, green deal, mobility, health, financial, energy, agriculture, public administration, skills:

- The HEALTH data space can be positioned in the high-high quadrant.

- The MOBILITY data space can be placed as lower benefits, but high effort of collecting/aggregating/analysing, because they are complex ecosystems.

- The SKILLS data space could be in the high benefit, but lower effort.

- The MANUFACTURING data space could be placed in the lower effort, but also lower direct benefit for society.

One can, of course, argue about the placement in the various quadrants. At the end of the day this is a political — in the highest sense — judgement call. As the technology evolves, things will shift along the two axes. But this should not stop policymakers from taking a strategic approach to regulating the data economy, because data has value!

If you want to learn more about this topic or have any questions, please contact or Massimiliano Claps, or drop your details in the form on the top right.